American Dipper

General Description

American Dippers, formerly known as Water Ouzels, are solid gray birds with slightly browner heads. Their beaks and eyes are dark, and their legs and feet light gray. They have short tails that are often cocked up. Dippers have white upper eyelids that are evident when they blink. Males and females look alike, and their plumage does not change appreciably during the year. Juveniles look like adults but may have white-tipped feathers.

Habitat

American Dippers are typically found in turbulent mountain streams within forested zones. They favor rocky substrates and clear, cold water, not unlike salmon. They can be found down to sea level, and up to alpine zones, as long as there are suitable streams. Dippers also occasionally inhabit pond or lake edges, or quiet sections of streams. During winter, they may show up in unusual habitats, but will most always be found in or near water.

Behavior

Dippers take their name from their characteristic bobbing. Unlike a Spotted Sandpiper or other tail-bobber, dippers move their entire bodies up and down. This bobbing, and the flashing of the white upper eyelid, may be visual communications that are important because of the loud environment that American Dippers tend to inhabit. Dippers catch most of their food under water, and jump or dive into frigid water to forage. They walk, heads submerged, along river bottoms, moving rocks to find prey underneath. The dipper takes prey from the water's surface while swimming, and will even use its wings to 'fly' under water. This bird will also fly through waterfalls. These birds are generally solitary and defend both summer and winter territories. Their calls and songs are loud, audible above the sound of rushing water.

Diet

Aquatic insects, especially larvae attached to river bottoms, make up the majority of the American Dipper's diet. They also eat other small aquatic creatures, including fish eggs and very small fish, and will feed at salmon spawning areas.

Nesting

Dippers are typically monogamous, but polygyny does occasionally occur. Nest sites are generally the limiting factor for breeding American Dippers, so a male with a territory that includes two appropriate nest sites may mate with two females. Dippers historically nested on ledges or banks along the sides of streams or behind waterfalls, and many still do. Now, however, nests are often found under bridges as well. Nests are large, mossy domes, up to a foot in diameter, and spray from the stream keeps the moss alive. The female chooses the nest site, and both members of the pair help build the nest, often dipping nesting material in the water before adding it to the nest. The nest has an outer shell of moss and grass, with a low entrance on a side facing the water. Inside is a cup made of grass, leaves, and bark strips. The female incubates 4 to 5 eggs for 13 to 17 days while the male provides food. Once the young hatch, the female broods them for about a week, and then joins the male in providing food for them. The young leave the nest at 24 to 26 days, and can swim and dive immediately after leaving the nest. The parents will often split up the brood and continue to feed the young for up to 24 days after they leave the nest.

Migration Status

American Dippers are generally resident, unless the streams they inhabit freeze. If that happens, they will travel short distances into the lowlands to find a new stream for the winter or move down-slope.

Conservation Status

Because much of the American Dipper population resides at higher elevations, information is lacking on range-wide population trends. Some development, e.g., bridge building, has been good for American Dippers because it has increased potential nest sites. Many other human incursions, such as deforestation and industrial and agricultural pollution, increase stream temperature and the amount of silt in the rivers, and both reduce the amount of prey in the streams. Dams and irrigation systems, which alter water levels, can also affect dipper habitat. Like salmon, which have many similar requirements, American Dippers are good indicators of stream health. Restrictions and restoration projects put in place to help salmon will also benefit American Dippers.

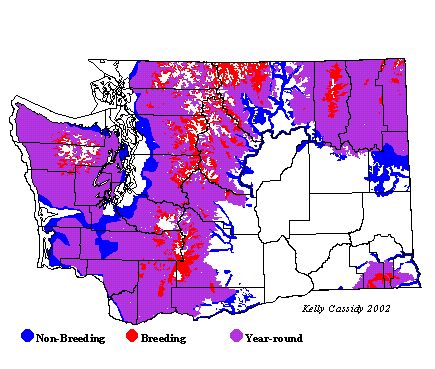

When and Where to Find in Washington

American Dippers are common year round throughout the mountainous areas of the state, and in many forested lowlands in western Washington out to the outer coast. They are most common at mid-elevations, although in winter they may become concentrated at lower elevations. They are rare, but may breed in the San Juan Islands. In the Blue Mountains of southeastern Washington, American Dippers are restricted to larger rivers. They are typically found up to or just over 5,000 feet in the Olympics, but have been found over 5,000 feet on Mount Rainier.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| North Cascades | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| West Cascades | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| East Cascades | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Okanogan | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Canadian Rockies | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Blue Mountains | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Columbia Plateau |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map